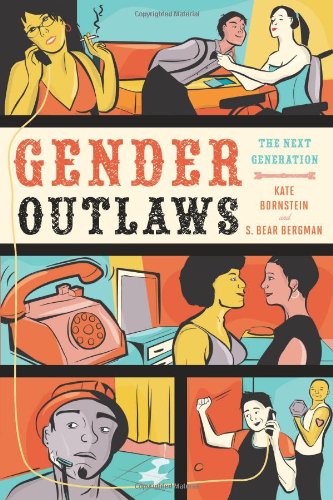

Cristy C. Road is a Cuban-American zine-maker, writer, illustrator, Green Day fan, Gemini and all-round bad-ass. She has published several illustrated books—Indestructible (2006), Bad Habits: A Love Story (2008), Spit and Passion (2012)—and is currently working on a tarot card deck and making music with her band, The Homewreckers. Road was part of the Sister Spit: The Next Generation Tour in 2007 and the POC Zine Project Race Riot! Tour in 2012.

Recently Bluestockings Magazine’s Co-Editor-in-Chief, Sophia Seawell, had the chance to talk to Road in a three-part interview series. In the first segment, Road spoke about zine-making, publishing, and the pernicious omnipresence of capitalism. In the second installment, Road talked about her relationship with the punk scene as a queer woman of color. In this segment, she’ll discuss themes of gender and sexuality as they overlap in her life and work.

To see some of her work visit her website.

***

![]()

Sophia Seawell: What you said earlier about the ‘kind of gay’ that is marketable makes me think about the ending of ‘Spit and Passion.’ It seems to me like you’re talking about the closet not necessarily as this awful, constricting place that you can’t wait to escape, but a place where you can figure out your own subjecthood. How do you feel are about the way in which the closet metaphor and the coming out narrative are talked about, and the former celebrated, in our culture right now?

Cristy Road: I think it’s awesome to talk about coming out, and I would love to write something about coming out to my family. I haven’t done that yet, and I probably will, but at the same time I don’t have that desire to. It was a happy and positive thing, but what led to it is what is more important to me, which was being in the closet for a million years and trying to survive it.

I do think it’s important to talk about these things from whatever angle, but when I started working on ‘Spit and Passion’ I didn’t have that much of a vision—it actually started as a sci-fi graphic novel about this world in the future that is exposed to radiation and there’s a lot of mutant happenings with animals and people. That world is socialist, and there’s a capitalist world in this dome. So I’m writing this story but I’m focusing on this character who happens to love Green Day and happens to be 12 and she’s in the closet. She was gonna have this internet romance with someone in the capitalist world, but then I keep writing about this character who loves this punk band and she’s gay and she’s this new world’s version of Latino so I was like, ‘I might as well just write about myself!’ So I started doing that kind of organically just because that’s what I felt like writing about.

And then those ‘It Gets Better’ campaigns started, and I thought they were weird and I thought they were unproductive. This is where the money is going as far as queer empowerment and media, this is where industries are putting their money: in this very assimilated safe propaganda for queerness. It was disappointing to see that. It was kind of the same as when gay marriage became legalized in New York and how that was seen as the primary struggle, like ‘Let’s put all our energy into gay marriage.’ But that’s not what we need right now. We need healthcare and transgender rights and less ‘gaystream’ (as the punks call it) and more justice for the queers who need that justice.

There’s already power in a lot of gay communities, but there’s still oppression, still places in the world where being gay is criminalized. So we still have to fight for these very basic rights, and for me it feels more important to give your attention and money and power to the people who don’t feel free, who don’t have this very happy ‘It gets better, I told my mom when I was 17 and everything was fine and she threw me party’ story.

SS: Right, for a lot of people coming out might mean risking being kicked out of their home, or for others being ‘out’ doesn’t change the fact that they don’t have healthcare and need it, or can’t visit their partner in the hospital. It reduces the narrative to pivot on one thing.

And speaking of gay marriage, I was really interested in the way you talk about religion and your relationship to it in ‘Spit and Passion,’ because mainstream feminist communities and movements in the U.S. have generally been pretty secular and framed religion as the patriarchal ‘enemy,’ an the obstacle between people and their liberation. Could you speak about how your religion and spirituality are part of your politics, if at all?

CR: I think the removal of religion from feminism is very white, that it comes from a very second-wave, white, privileged feminism where spirituality doesn’t matter. Everyone’s hailing the goddess but for some reason we’re not allowed to identify as Catholic. So in these communities where culture is more important than queerness, in a lot of situations we want to hold on to the spirituality. Taking away all the power from celestial bodies, your ancestors and nature is so patriarchal! That’s where capitalism came from! So much feminism and anarchism is perpetuating patriarchy by removing spirituality, because you’re taking away everything that came before you, you’re taking away the earth where you live, you’re taking away native beliefs, things that existed in indigenous native communities before slavery, before colonialism. Growing up in a family that was Latino, we cared about spirituality and ancestry was very sacred—and there is a lot of spirituality that exists in white communities and different communities all over the world, but as far as feminism and anarchism and anti-capitalism… For me at least, in order to find anti-capitalist work or ideas that are spiritual, I feel like I always end up going to people who might not even identify as anti-capitalist but just are—like witches. Las brujas.

If you don’t have the ancestral connection to whatever native culture or spiritual culture or witchcraft or whatever you want to call it but you’re still spiritual and connected to the idea of a goddess or to tarot or astrology, I think that’s really awesome. And that definitely exists, but it’s still very compartmentalized within the radical feminist third wave community. I have been in situations where I go to an anarchist punk event and I start talking about spirituality and reclaiming the Virgin Mary—because I’m Latina, and honoring spirits is about honoring your ethnicity and your culture—and it’s really annoying that if it’s a predominantly white space and they’re anarchist or anti-capitalist and don’t care about gods, then I feel like that’s racist, and if I straight up say that in those spaces, nobody wants to deal with me or they deal with me in a like ‘Oh my God, she’s scary let’s just let her talk about her god’ way.

SS: That’s the thing! Do I not say anything or do I say something and put up with the bullshit that I’m going to get in response? Because both can be really exhausting.

CR: Totally, you just want to hide in your safe space with your fucking brujas.

SS: Speaking of safe spaces, you talk about your family as providing that for you. From the images and descriptions in ‘Spit and Passion’ it seems like you were in a predominantly or only-female household, and earlier you mentioned that you talked about capitalism and sexism at home. How much were issues of gender oppression part of your consciousness as you were growing up?

CR: The idea of women’s empowerment was handed to me because I was surrounded by all working women who worked a bunch of jobs. There were no men. My dad left when I was very young. There were other men here and there, and I ended up having a step dad for a while, and he was rad, but there was still so much power in the femaleness in my upbringing. Like my grandma—everyone revolves around the grandma! I always lived with my mom, my aunt and my grandma, and I had another who was next door, so I felt like I grew up around really intense female energy even despite the fact that I couldn’t be queer and that the butchness of my preteen years was kind of frowned upon. And sometimes it still is, you know? I’m growing my hair out and some family members are a little too excited about it, and it’s like—

SS: ‘I’m not doing this for you.’

CR: Yeah! I’m like, ‘Actually, I’m actually doing this so I can dress more butch and feel centered.’ Right now I have this short hair so I want to wear lipstick and cleavage every single day. I want a ponytail and a butch shirt and I’ll button it all the way to the top and that’s what I’ll wear on Christmas.

So I did grow up with all these ideas of feminine power and there wasn’t much body-shaming, it was very comfortable. It’s a Latin family so it’s like ‘You’re losing weight’ or ‘You’ve gained too much weight’ and you’re never perfect, but there’s still this appreciation of curves and food.

![]()

SS: In ‘Spit and Passion’ you describe ordering hot wings and wearing men’s clothing so I was wondering how you see or experience the overlap of gender and sexuality. They can be talked about as discrete things but they seemed intertwined in your book.

CR: They felt intertwined. They don’t anymore because now I have all this language for identifying as queer and dating women or transgender men or genderqueer people, and that part of my gayness is just about who I’m with and how I experience sexuality. My gender presentation is this whole other thing. I’m older and I feel empowered by both of these things—I can experience them separately. Of course they end up merging when it’s like ‘I’m dating a femme and she wants me to be more butch and I don’t want to’ but as a kid it felt like the same thing: ‘Ew, you like girls’ or ‘Ew, you’re dressed like a boy.’ It’s all the same and it’s all gross. So as a kid I definitely didn’t know how to separate the two experiences. Because it was also this thing where when I would find myself attracted to a masculine person or a boy, I wouldn’t know what to do, because it was the 90s—‘bisexual’ wasn’t a thing, ‘pansexual’ wasn’t a thing, especially to a 12 year old in a super conservative city. It was just all very mixed for me as far as experiencing gender and experiencing sexuality and then it kind of just started making more sense to me the older I got and the more I isolated myself from the conservative communities and I started hanging around more punks and more queer punks and more women.

In punk rock there’s so many butch-looking women who are straight as all hell, straight women who look super masculine, and that was always really awesome to me. I also saw that in hip-hop in the 80s—that women could be super butch and still be straight, and that’s awesome. That’s what I appreciated about punk; that helped me coexist with my queerness and my weird gender that goes back and forth all the time. And I’m now, I’m 31, and I feel the most able to be kind of butch, but mostly femme, but I have a weird voice and sit like a man sometimes. I have very, very masculine traits. My mom doesn’t notice and my best friend doesn’t notice, she always says ‘You can’t help it, you’re so girly’ and I’m like, ‘I don’t really think so.’ I don’t know, I don’t feel it. But I feel it when I’m in a relationship with a masculine person, for example. I feel my femme identity more only because I’m being compared to the masculine. But in regular life, walking down the street talking to people, I feel like my femininity is more of an outfit choice. I identify as cisgender because my female gender identity and my anatomy and experience and all that stuff, it’s queer but I definitely relate all that stuff to identifying as a girl and identifying as female.

SS: There’s so many different moving parts: there’s the gender I was assigned at birth based on my anatomy, there’s the way I was socialized, there’s my gender presentation, there’s the people I’m attracted to, and of course society tells us they’re all supposed to align in this binary heteronormative way.

CR: And then there’s intense femmephobia in the feminist communities, and especially in punk. As I was saying, hella butch straight girls, and when those butch straight girls would give me shit for wearing lipstick and a mini skirt it’s like ‘Oh great, there’s still patriarchy in feminism.’ There have always been so many hurdles to jump through and I feel like I feel normal now because I have a queer community that’s very femme-centric. In my queer community, there’s a large presence of transmasculine people and femmes and none of us were part of a lesbian community because we felt awkward or felt too femme or we were ‘confusing.’ There’s so much patriarchy that still exists in ‘feminist’ communities. I’m not even gonna start talking about Cathy Brennan and all that lesbian separatist and Michfest [Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival]. When there isn’t justice for trans women–

SS: Then you’re just perpetuating gender oppression.

CR: Yeah and I don’t really think there’s a way around it. Like, I’m done. You know how if there’s an older person and they don’t get queerness and someone’s like ‘bear with them, they’re 70,’ I can’t really do that sometimes. I can’t bear with anyone, especially lesbian separatists. I understand that they went through some shit as lesbian in the 70s but how do you think trans women feel?

Interview with Cristy C. Road, conducted by Sophia Seawell, Co-Editor-in-Chief

Images Courtesy of Cristy C. Road

![]()